This article traces the history of the concept of suffering in order to understand how beliefs about suffering and the pain of suffering affected society and shaped the meaning of suffering. We end with a review of the meaning of suffering in the present day, when the role of suffering has been reformulated because of new events, risks, threats, and implications.

This article traces the history of the concept of suffering in order to understand how beliefs about suffering and the pain of suffering affected society and shaped the meaning of suffering. We end with a review of the meaning of suffering in the present day, when the role of suffering has been reformulated because of new events, risks, threats, and implications.

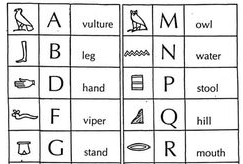

Hieroglyphics, Ancient Civilization & the History of Suffering

The picture in the upper left shows several symbols and their meanings from ancient Egyptian hieroglyphics in about 700 BCE. Two drawings, the vulture and the viper, were hieroglyphic symbols of suffering. One was a drawing of a deadly viper, whose poison caused suffering and sometimes death. The other drawing symbolized a huge bird that feeds on animal remains left by predators. These symbols convey that suffering can be deadly, which leaves behind great hurt, and which we label as grief, loss and sorrow. What is implied is these early formulations of suffering is that life begins and ends in suffering.

Suffering as Knowledge

As language developed, the concept of suffering evolved to support more elaborate and complex conceptions of suffering. Ancient societies such as the ancient Greeks had similar mythologies to explain the origin and consequences of suffering and death. It is especially intriguing that one of the first ideas about the meaning of suffering was the Early Greek notion of suffering as the origin of knowledge. The Garden of Eden story of the origin of human life and sin supports this extreme position that suffering is the origin of knowledge. The mythology supporting the notion of suffering as knowledge tended to highlight carnal knowledge to illustrate how knowledge is not necessarily a desirable good.

Additional discussion of the history of suffering will be structured in terms of the evolution of different perspectives on suffering and its role in human life and human society. The perspectives include 1) suffering as punishment, 2) suffering as reward, 3) suffering as craving, and 4) suffering as the gateway to happiness.

Suffering as Punishment

The first perspective, suffering as punishment, was predominant from the earliest historical periods down through the Middle Ages. During both the era of animist religions and the early era of organized religions (including Judaism, Christianity, and Islam), pain and suffering were attributed to higher powers (Bowker 1970; Dormandy 2006; Kruse & Bastida 2009). God or the gods were thought to determine when, where, how, and what suffering was distributed among human beings. Punishment was doled out as an indication of super-natural displeasure with humans’ attitudes and behaviors. ‘Suffer’ once implied the long-suffering or patience—necessary to cope with the severe and sometimes arbitrary suffering of everyday life. By aligning their behavior with what they saw as the will of God or the gods, people believed that they were maximizing their relief from suffering. There will still be many people today who frame suffering primarily as punishment.

Also from the same traditions came the story of Job in the Old Testament. Job effectively was a victim of torture for the purpose of establishing that suffering is possible without the need to punish for sinful behavior. The main point of the story of Job’s intense suffering was that he benefited from some of it, not just in terms of redemption, but from greater empathy and understanding of others.

Suffering as Craving

Early Hinduism and later Buddhism claimed that suffering arose from Samsara, the human life cycle, and that suffering followed failure to follow the path to enlightenment. Buddhism directly teaches that ‘Pain is inevitable; suffering is optional,’ and ‘the origin of suffering is craving.’ Craving is interpreted by some as egocentric habits of mind (Targ and Hurtak 2006). The Buddha warned that all pleasurable sensations lead to craving and craving can take root (Dalai Lama 2011; Dalai Lama and Goleman 2003). Attaching to that craving causes suffering (as with addiction). Thus, the Buddha advocated the Middle Path, which avoids the extremes of a life of unrestrained pleasure-seeking and a life of extreme denial and suffering (Nikaya 1971). Buddhist practice consists of learning to live without specific pleasures by engaging in mindfulness and loving kindness for all living beings. Mindfulness is a meditative practice intended to keep the mind from its tendency to cling to emotions such as anger and hatred and to entertain thoughts of retribution and self-pity (Siegel 2010). As a Buddhist takes up this life of mindfulness and contemplative practice, cravings are less able to take root (Bernhard 2010).

The perspective for suffering as craving remains a popular attitude toward suffering in both Eastern as well as Western cultures. Equivalent notions of ‘addiction as suffering’ and ‘unrestrained pleasure’ as suffering are common in most religious traditions.

The following quote is attributed to Socrates: “If you don’t get what you want, you suffer; if you get what you don’t want, you suffer; even when you get exactly what you want, you still suffer because you can’t hold on to it forever” (Millman 2006). Millman gives this notion a western psychological slant with “Pain is objective and physical; suffering is our psychological resistance to such events” (2006). As noted by Hurst (2011), Merton (1961) taught “contemplation as a way of living in awareness, allowing us to integrate suffering into life.” Aristotle advocated a middle way between excess and asceticism, not unlike Buddha’s middle path (Shields 2012).

In more recent times, the theme of suffering as knowledge is linked to the perceived benefits of suffering. Suffering is one of the few routes to maturity and wisdom. McGonigal (2016) and others claim that stress and modest suffering offer major pathways to personal understanding, growth, and resilience. Thus, what originally was a state of mind to be avoided, eventually became a state of mind and experience to be sought after and appreciated.

Another metaphor for this process is uniting with a greater universal consciousness. Other religions try to define rules or standards for people to balance pleasure with indulgence such that addictive craving is avoidable. Few are effective, though, because anger, greed, over-indulgence, and other types of suffering that result from craving are commonplace, if not rampant, in most societies (Pruett 1987). For Buddha, the path to happiness started from an understanding of the root causes of suffering.

Suffering as Reward

The second perspective, suffering as reward, first emerged from the punishment perspective. Although suffering was interpreted as a sign of displeasure from the supernatural, it was also seen as a reward. A divine power indicated which behaviors were off-limits. This meant you could avoid future suffering by avoiding the behavior that brought on your suffering. Some religious groups have even presumed that, because we can learn from suffering, it is a desirable, laudable condition that should be exalted (Ashwell 2011; Beke 2011; Ghadinian 2012).

In the 13th century, groups of Roman Catholics, known as the Flagellants, took this practice to its extreme ends, marching through the streets whipping themselves. After several deaths, the Church officially withdrew its approval of these events (Bean 2000). Still, some contemporary religions will celebrate holy days devoted to suffering.

Adherents, too, believe that withstanding pain is a holy act, so using medications or other sources of relief is less desirable than fully experiencing suffering. Author and Trappist monk Thomas Merton (1955) said, “We must see suffering not as a destructive power but as a transcendent gift from the Divine.”

Ironically, we could even see the exalting of suffering in the 2012 presidential campaign in the United States. During a Republican primary forum, four candidates took turns telling their story of extreme suffering and how it had made them a better Christian and closer to God. One candidate even said, “Suffering… is not a bad thing, it is an essential thing in life” (Jacoby 2011). Unfortunately, this belief in suffering as a good leads many to take a stand against government funding for the poor and others who suffer the most.

New institutions in western legal systems also indirectly support the perspective that suffering is a reward. In the United States, tort cases in which people seek compensation for pain and suffering tend to result in considerable economic payoff (Rodgers 1993). Conventional norms in the legal and insurance systems for different types of suffering even provide guidelines for the economic payment due families for the death of a family member. Logically, the idea is that victims did not bring their suffering upon themselves, and so someone responsible should bear the ‘punishment’ in the form of a financial payment or other settlement.

Suffering as the Gateway to Happiness

In Hindu, suffering or dukkha, means the physical, mental and emotional instability and afflictions that arise from the dualities and modifications of the mind and body. These modifications manifest variously in human life as pain and suffering, attraction and aversion, union and separation, desires, passions, emotions, aging, sickness, death, rebirth, etc.

According to Hinduism, suffering is an inescapable and integral part of life. The purpose of religious practice in various schools of Hinduism is to resolve human suffering that arises from samsara, which in a specific sense means the cycle of births and deaths and in a general sense, transient life. As long as we are caught in the phenomenal world of transient objects and appearances, we become attached to them and have no escape from suffering.

All of us experience profound levels of suffering in our lives. It’s eventual alleviation creates the possibilities for happiness. The founder of the Bahai Faith said, “Suffering is the gateway to happiness.” Research in the psychology of resilience supports the conclusion that a modest level of suffering inoculates us from succumbing to suffering. This would be a panacea were it not for the fact that the mechanism does not work for cases of extreme suffering.

Relief of Suffering as Human Purpose

The principle purpose of many (if not most) humans is self-promotion. They hope to obtain (or maintain) comfort, power, popularity, and wealth. Some, though, are driven primarily by a feeling of moral responsibility for others’ wellbeing (Kleinman and van der Geest 2009; Mayerfeld 2005; Tronto 1993; Williams 2008). The most common literary symbol of such a commitment to others is the Christian Good Samaritan—people with humanitarian commitments to helping others, no matter their race or stature, are sometimes called good Samaritans. A similar sentiment motivates a recent campaign to get hundreds of thousands of people (regardless of faith) to commit themselves to the Charter for Compassion (Armstrong 2011).

For those whose purpose is love, compassion, or helping others, suffering provides a basis by which to prioritize limited time and attention (Johnson & Schollar-Jaquish 2007). Helping those who suffer more is generally seen as more fulfilling. Further, since the traditional definition of compassion is a desire to relieve another’s suffering, this work becomes the yardstick by which to measure an authentic life; suffering is an indirect source of meaning in the Samaritan’s life. Contributing to humanity in this sense could mean helping a few close friends or all seven billion people alive today.

The mission to relieve suffering does not require one-to-one contact. It can be accomplished by providing time and resources to global relief organizations. By giving to varied causes or helping a variety of different types of people in need, you increase the likelihood that your pro-social actions will have benefited a person or several people. While positive feedback is not mandatory for gaining purpose and satisfaction from compassionate actions, it does help prop up and support the energy put into reducing the suffering of others.

Relief of Social Suffering as Progress in Quality of Life

The process of meaningful relief of others’ suffering, as discussed in the preceding section, applies to this perspective as well. When you are relieving another’s suffering, you are also improving their quality of life. This perspective is uniquely justified by its emphasis on quality of life as a concrete human need and its emphasis on social suffering as a qualitatively different type of suffering.

Several decades ago, anthropologists and sociologists began to explore the meaning of suffering and the structural forces of society compounding suffering’s damage on the world. Many of these scholars came to label their focus as social suffering. This was a much-needed development because most scholars were treating suffering as only a product of the individual rather than the social, and as idiosyncratic rather than structural.

As a common phrase, ‘quality of life’ (QOL) goes back only a few decades. However, in the twenty-first century, the concept has become rather popular, especially within research on health and economics (Land et al. 2012; Mukkerjee 1989). There is even a professional group called the International Society for Quality of Life Studies, and it publishes several journals with ‘quality of life’ in their titles. Many national and international policy reports also use the phrase, sometimes equating it with general well-being and/or happiness (Jordan 2012). The governments of several nations are now using the concept in attempting to construct new measures of national or human progress.

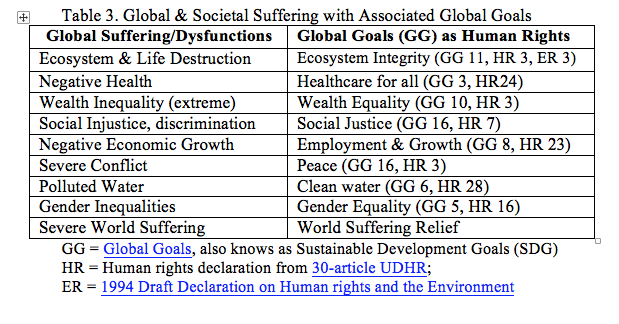

Relief of Suffering as Progress in Human Rights

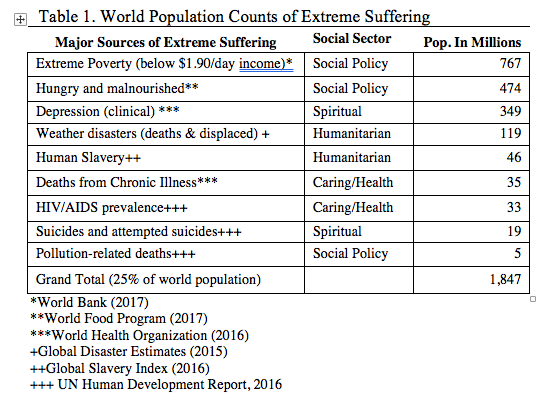

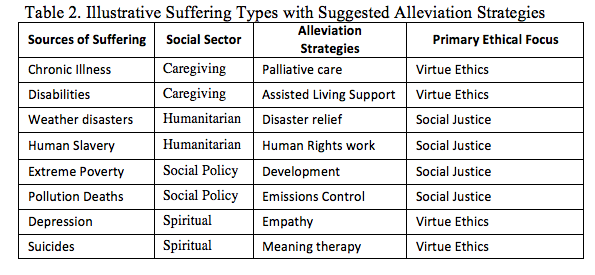

Recently, I discovered the concept of suffering serves as a “missing link between human rights and global goals.” What I mean by that is this. The UN Global Goals, which are a mere re-statement of the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals, are associated closely with human rights as officially declared in one of the official declarations of human rights. This relationship between suffering, goals and human rights is illustrated in the Table within the article on this website called “Setting Priorities…”

Intense human suffering that violates specific human rights provides a more compelling rationale for the human right than does the traditional ‘natural rights’ argument. Human rights are legitimated by their intimate link to suffering within this framework. Because of this intimate association between human rights and suffering, relief of extreme global suffering has moral priority over enhancing the general well-being of the population. This is particularly important because the core Global Goals define priority purposes and meaning for the planet.

These conclusions may seem to veer away from the goals of scholarship toward that of policy, but a better way to view it is that the field of QOL has more to contribute to policy than it now delivers. And principles of the moral order of both local communities and the global society need to be incorporated into both scholarship and practice in QOL.

Living beings everywhere desire above all else to find personal meaning and happiness and to be free from suffering. Yet, because we do not have a deep understanding of the nature of these states, our grasping for happiness only seems to lead us into more suffering.” This is a rephrasing of Ancient Buddhist wisdom.

Human rights norms are primarily focused on preventing the worst forms of human suffering. According to bioethicist Andorno (2013), preventing extreme human suffering has moral priority over the promotion of the maximum well-being for a given population. This might change if the concept of well-being evolved more toward social caring and personal meaning.

Conclusions

Deep understanding of suffering remains elusive, but even concepts like happiness and well-being suffer from imprecision. Our principal goal is to not only to build a scholarship of human suffering, but we seek to identify what will be required to alleviate various types and quantities of suffering. Ultimately, we need to know much more about how to reduce suffering and to increase well-being such that decision makers can allocate resources that create better societies. Policy makers need not only evaluation data, but they need to know the moral implications of different strategies.

The concept of suffering has its weakness as does the concept of well-being. Societal betterment requires relief and reduction of extreme suffering from any source or cause. The conceptual weakness of this argument is that there is no obvious distinction between modest or major suffering and extreme suffering.

Most use of the word suffering references milder forms of suffering. But it is extreme suffering that implicitly calls for attention and amelioration. Unfortunately, little work has been done on distinguishing those two types of suffering. This dichotomy is critical to answering two questions: 1) When does suffering benefit us by building resilience? 2) When is suffering alleviation more important than the well-being of the general population? The best answers to question 2 are when suffering is extreme or when well-being is low. Thus, progress in measurement is important to the future of both suffering and well-being as theoretical constructs.

Progress in the concept of suffering since ancient times has been possible as mythologies and ignorance are being replaced by advancing knowledge, especially with regard to resilience. In addition, due to the increasing role of human rights in promoting better quality of life, the value of human rights has become move obvious. This is particularly true with respect to our understanding in the modern era of the true nature of suffering.

References

Adorno, R. (2013). Principles of international biolaw: Seeking common ground at the intersection of bioethics and human rights. Brussels, Belgium: Bruylant Publishing.

Anderson, R. E. (2014). Human Suffering and Quality of Life -Conceptualizing Stories and Statistics. NY: Springer.

Anderson, R. E. (Ed.) (2015). World Suffering and the quality of life. NY: Springer.

Anderson, R. E. (Ed.) (2017). Alleviating World Suffering: The Challenge of Negative Quality of Life. NY: Springer.

Armstrong, K. (2011). Twelve steps to a compassionate life. New York: Anchor.

Ashwell, R. (2011). Suffering and the way. Parabola, 34(1, Spring), 58–61.

Bean, J. (2000). Flogging. Emeryville, CA: Greenery Press.

Beke, J. (2011). Intentional suffering. Parabola, 34(1, Spring), 68–71.

Bernhard, T. (2010). How to be sick—A Buddhist-inspired guide for the chronically ill and their caregivers. Boston, MA: Wisdom Publications.

Bourdieu, P. et al. (2000). Understanding. In P. Bourdieu et al. (Eds.), The weight of the world: Social suffering in contemporary society. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Bowker, J. (1970). Problems of suffering in religions of the world. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Dalai Lama (2011). To be free of suffering, Parabola, 36(1, Spring), 26–30.

Dalai Lama, & Goleman, D. (2003). Destructive emotions—How can we overcome them? New York: Bantam Books.

Dormandy, T. (2006). The worst of evils—The fight against pain. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Farmer, P. (2005). Pathologies of power: Health, human rights and the new war on the poor. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Ghadirian, A.M. (2012). Creative dimensions of Suffering. Minneapolis, MN: BookMobile.

Hurst, V. (2011). The flight from disunity: Thomas Merton on suffering. Parabola 34(1, Spring), 34–39.

Jacoby, S. (2011). Christian politicians exalt suffering in GOP campaign. The Washington Post (23 November) http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/spirited-atheist/post/christian-politicians-exalt-suffering-in-gop-campaign/2011/11/22/gIQAa9HVoN_blog.html. Accessed 27 January 2013.

Johnson, N., & Schollar-Jaquish, A. (Eds.) (2007). Meaning in suffering—Caring practices in the health professions. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press.

Jordan, T.E. (2012). Quality of life and mortality among children. New York: SpringerBriefs.

Kleinman, A. (1988). The illness narratives: Suffering, healing and the human condition. New York: Basic Books.

Kleinman, A., & van der Geest, S. (2009). ‘Care’ in health care: Remaking the moral world of medicine. Medische Antropologie, 21(1): 159–168.

Kleinman, A., Das, V., & Lock, M. (Eds.)(1997). Social suffering. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Kruse, N., & Bastida, E. (2009). Religion, suffering, and health among older Mexican Americans. Journal of Aging Studies, 23(2), 114–123.

Land, K.C., Michalos, A.C., & Sirgy, M.J. (2012). The development and evolution of research on social indicators and quality of life, In K. Land et al. (Eds.), Handbook of social indicators and quality of life research (pp. 1–22). New York: Springer.

Mayerfeld, J. (2005). Suffering and moral responsibility. NY: Oxford University Press.

McGonigal, K. (2015). The Upside of Stress: Why Stress Is Good for You, and How to Get Good at It. NY: Penguin Publishing Group.

Merton, T. (1955). No man is an island. New York: Harcourt, Brace Jovanovich.

Merton, T. (1961). New seeds of contemplation. New York: New Directions.

Millman, D. (2006). The journeys of Socrates: An adventure. New York: HarperOne.

Mukherjee, R. (1989). The quality of life—Valuation in social research. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Nikaya, S. (1971). The word of the Buddha. Kandy, Sri Lanka: Buddhist Publication Society.

Pruett, G.E. (1987). The meaning and end of suffering for Freud and the Buddhist tradition. Lanham, MD: University Press of America.

Rodgers, (1993). Estimating Jury Compensation for Pain and Suffering in Product Liability Cases Involving Nonfatal Personal Injury. Journal of Forensic Economics 6(3), 251-262.

Shields, C. (2012) Aristotle. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. N. Z. Edward (Ed). http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2012/entries/aristotle/. Accessed 13 May 2013.

Siegel, R.D. (2010). The mindfulness solution. New York: The Guilford Press.

Targ, R., & Hurtak, J.J. (2006). The end of suffering—Fearless living in troubled times. Charlottesville, VA: Hampton Roads Publishing.

Tronto, J.C. (1993). Moral boundaries: A political argument for an ethic of care. New York: Routledge.

Upton, C. (2011). Metaphysics of suffering. Parabola, 34(1, Spring), 72–83.

Williams, C.R. (2008). Compassion, suffering and the self: A moral psychology of social justice. Current Sociology, 56(5), 5–24.

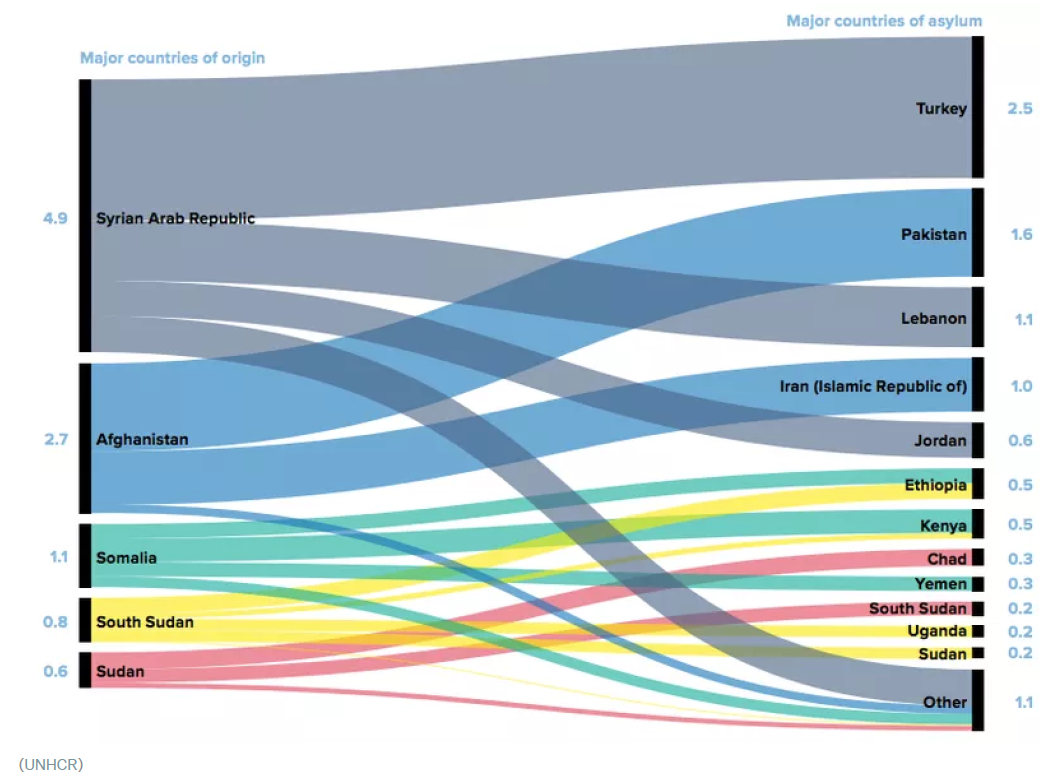

South Sudan became an independent nation in 2011, but within the year, armed conflict began between warring clans and ethnic groups, who are affiliated with different presidential candidates. The conflict has been brutal with armies on both sides of the conflict committing genocide-like slaughter.

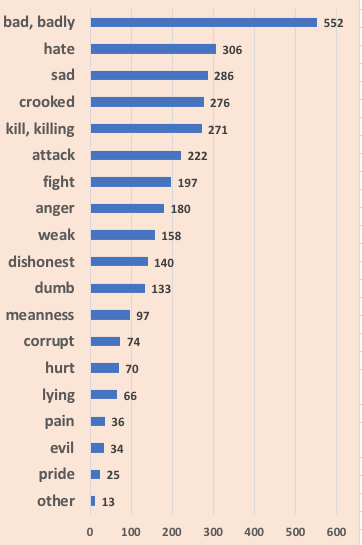

South Sudan became an independent nation in 2011, but within the year, armed conflict began between warring clans and ethnic groups, who are affiliated with different presidential candidates. The conflict has been brutal with armies on both sides of the conflict committing genocide-like slaughter. Donald Trump is the first President to use Twitter to regularly communicate with his public. As of late 2019 he has released over 40,000 tweet messages.

Donald Trump is the first President to use Twitter to regularly communicate with his public. As of late 2019 he has released over 40,000 tweet messages.

The United Nations High Commission Refugees (UNHCR), in partnership with Google launched a website called Searching for Syria. (

The United Nations High Commission Refugees (UNHCR), in partnership with Google launched a website called Searching for Syria. (

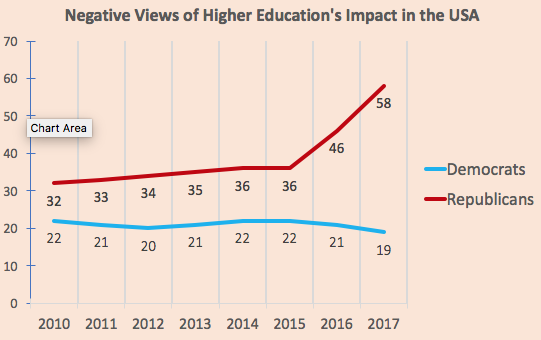

The Pew Research Survey of American adults in June 2017 discovered a disturbing trend: most (58%) of the Republicans gave a negative view of higher education (“colleges and universities.”) In stark contrast, only 19% the Democrats agreed with the negative answer to this survey question: “Do you believe that colleges and university have a negative or positive effect on the way things are going in the country?” Incidentally, the survey included “leaners” (those saying they lean toward Republicans or toward Democrats) in each political group.

The Pew Research Survey of American adults in June 2017 discovered a disturbing trend: most (58%) of the Republicans gave a negative view of higher education (“colleges and universities.”) In stark contrast, only 19% the Democrats agreed with the negative answer to this survey question: “Do you believe that colleges and university have a negative or positive effect on the way things are going in the country?” Incidentally, the survey included “leaners” (those saying they lean toward Republicans or toward Democrats) in each political group.

The parable of the Good Samaritan as told by Jesus Christ in the New Testament (Luke 10:25-37) has become a litmus test of sorts for humanitarianism. The Good Samaritan serves as a metaphor for the responsibility and duty of compassionate persons to care for others that need serious help. If you adopt the altruistic approach of the ‘Good Samaritan,’ you are enacting the teaching of Jesus to “love your enemies.” You are also implicitly defending humanitarianism.

The parable of the Good Samaritan as told by Jesus Christ in the New Testament (Luke 10:25-37) has become a litmus test of sorts for humanitarianism. The Good Samaritan serves as a metaphor for the responsibility and duty of compassionate persons to care for others that need serious help. If you adopt the altruistic approach of the ‘Good Samaritan,’ you are enacting the teaching of Jesus to “love your enemies.” You are also implicitly defending humanitarianism. This little essay in 1,000 words explains why one American demographic wallows in such deep despair that its life expectancy has been growing shorter. While addictions have largely been blamed, I argue that these stresses arise out of a loss in meaning by a culture caught in consumption.

This little essay in 1,000 words explains why one American demographic wallows in such deep despair that its life expectancy has been growing shorter. While addictions have largely been blamed, I argue that these stresses arise out of a loss in meaning by a culture caught in consumption.