Hate and hatred describe extreme dislike at a deep emotional level. Anything can be the object, but we suffer most when the object of hate happens to be a person or a people. We all suffer more from social hating because so often it forms the platform from which prejudice and discrimination, if not torture and other inhumane actions, spring and spread to others.

Hate and hatred describe extreme dislike at a deep emotional level. Anything can be the object, but we suffer most when the object of hate happens to be a person or a people. We all suffer more from social hating because so often it forms the platform from which prejudice and discrimination, if not torture and other inhumane actions, spring and spread to others.

Typically, anger and prejudgment gang up around an object of hostility, which leads to mobilizing attacks against the presumed perpetrator. Such attacks may be verbal and/or physical including killing, torture and other inhumane actions. This essentially describes the model of hate outlined by psychologist Aaron Beck in his 2010 book, Prisoners of Hate.

Not only does hatred eat away at our virtues and other mental states, but it can make us more susceptible to physical diseases and injuries due to fighting and war. Researchers have discovered a “hate circuit” in the brain that maps the parts of the brain affected by hate and the decision to act upon that hate. Other researchers found that even short periods of hatred lead to greater immune deficiency.

People sometimes minimize hatred because they concentrate upon anger alone. Negative feelings first evolve into anger as annoyance and hostility arise from not getting what was wanted or expected. Then as one not only feels upset by another person, but attributes blame to that person, the negative emotions escalate to hate, which is intense or passionate dislike that not only arises from hostility but a desire for revenge.

Perhaps the most devastating consequence of hate appears when neither anger nor hate can be contained. Hate escalates or deepens when the hater accuses the other person(s) of guilt and complicity. Then feelings and a desire for revenge intensify because the other person’s actions are interpreted as moral transgressions. How else could a mob stone a woman to death because of sexual behavior; or hang a black man from a tree on the basis of a rumor nobody checked out.

Hatred and Violence in a Texas Church

This past weekend, on November 5, 2017, Devin Patrick Kelley at the age of 26, killed 26 people at church in a tiny town in Texas. Millions of people watched thousands of hours of radio and television time with hundreds of journalists speculating about the motive of the shooter.

Yet, the shooter had multiple motives, one of which was deep hatred and intense anger. Even after the news media discovered that the shooter had feelings of revenge against his former mother-in-law, who attended that church, the media still never mentioned the word hate. Nor did the media mention much about irresponsible failure to curtail acquisition of automatic rifles (machine guns) as a cause of the tragedy.

The President and many others said the problem or cause was mental illness. Underlying this premise was the presumption that anyone with such anger and hatred would necessarily be mentally ill. Yet, if anger and hatred really do indicate mental illness, then the nationalists and racists that occupy the White House are mentally ill.

Why are the media producers afraid to allow talk of hatred, anger and a culture of violence as causes of the mass murder? Even after uncovering that the shooter had, in anger, nearly killed his former wife, his infant son, and a dog with his fists, they still did not acknowledge that Kelley was driven by anger, hate and revenge.

Why don’t we think to blame a violent person’s killing on what the perpetrator was feeling, namely extreme hatred intertwined with deep anger? Hatred and inability to regulate one’s own hatred are two of the major root causes of violence.

Leon Fink in the December 2017 issue of In These Times, note that after major disasters, American media focuses the majority of its on-air time on stories of grieving families, heroic deeds and collective sympathy. He concludes that the broadcast and print media both “neglect the power of the people as a whole to effect change. The public sphere and the community are presented as weak, absent or feckless.”

Hate Crimes

Hate crime, also known as bias-motivated crime, refers to harm done toward others who are perceived to be members of a social group seen as undesirable. Often victims of hate crimes are racial minorities or members of an unusual gender identity group.

Omar Mateen, a 29 year- old man who murdered 49 people and wounded numerous others in Orlando, hated gays and those identifying as transgender. A New York Times article indicates, the shooter had a chilling history that included talking about killing people, beating his former wife and voicing hatred of minorities, gays and Jews.” In this case, the patrons of The Pulse, a Gay club in Orlando who were enjoying an evening of revelry, when shots rang out, were part of the LGBTQ community and the majority were Latino.

Healing Hatred

The most important question is how hatred can be healed and replaced by positive emotions. Starting first with the big picture, societies that purposely develop social solidarity have a major advantage over loosely knit communities and societies. Social solidarity reinforces humane values such as caring and compassion.

Unfortunately, many of us find ourselves in hate filled neighborhoods and societies where hatred continues to grow or fester. And we do not have the luxury of educational systems that always protect our children from become immersed in hatred, prejudice, and discrimination. Never-the-less, there are paths that can be taken to escape at least some of the hatred around us.

Aron Beck in Prisoners of Hate identifies some strategies for escaping the clutches of hatred. One is to consciously deactivate the hostility mode whenever it is triggered; another is to avoid thinking in terms of dichotomies such as good and evil; and thirdly, remember that most beliefs underlying social discrimination are based upon inaccurate, untrue beliefs or stereotypes.

One of the best methods for escaping the clutches of hatred is through spiritual contemplation or meditation. For example, Buddhist meditation practice starts with allowing any thoughts and memories to arise into consciousness. As memories of hatred arise spontaneously, they can be consciously examined and then dismissed out of mind. Practice in such exercises has the potential to begin to heal the destruction caused by hateful thoughts and feelings.

Finally, the routine practice of forgiveness indirectly reduces hate. Hatred and forgiveness cannot co-exist because each one is logically incompatible with the other.

Hate at the Global or Macro Level

A recent article on this website, entitled Setting Priorities for Amelioration of Global Threats, and another entitled A New Framework for Suffering-Alleviation, offer a conceptualization of goals and risks that makes it easier to set priorities for global policy and action. This briefly expands on that framework with the focus upon hatred as a major underlying cause of some major global problems.

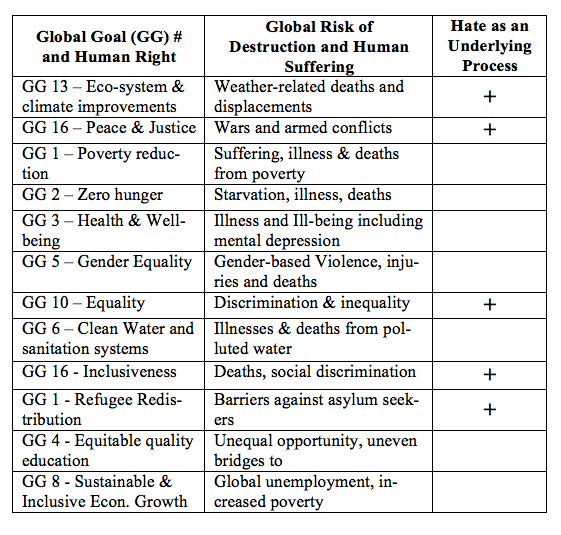

Even though estimation of the magnitude of world suffering remains rather primitive, it still reveals an enormous amount of suffering globally. The framework implicit in the following table identifies various types of global suffering, each one tied to a global goal that has already been identified as a high priority human right. Each global goal and its row in the table represent a separate source of human suffering, if not now, in the future.

The entire set of global risks contained within the list in the Table would represent the totality of suffering except that this is a short list and the amount of suffering attributable for each source overlaps with other sources.

Our main concern here is the extent to which hatred, and the violence that follows, account for the suffering associated with the risk inherent in the global goal. Hatred serves as an underlying process for several of the global risks including climate displacements, wars and armed conflicts, social inequality, social discrimination and barriers against asylum seekers.

This is a cursory glance at some core sources of suffering associated with major global goals as defined by major sectors of the United Nations. The institutional arenas associated with five of the goals targeted to alleviate associated suffering are infused with problems like racial discrimination and barriers to the entry of immigrants. In other words, institutional hatred is a barrier to the reduction of suffering resulting from such unsolved world problems as racism and extreme nationalism.

A final conclusion from this analysis is that the healing of hatred is a challenge that needs to be addressed at all social levels. Starting with the individual and the interaction of couples and going on up to nations and the world, each of these levels of global society is made worse by individual or social hatred.

As many people add to the suffering generated by hatred of various types at the larger levels of society, it is easy to disown the problem. Rather than try to hide from the problem of hatred, we as individuals should stop and reflect whenever we feel hatred or anger arising. Then we can focus our attention on the hate until it releases, which then makes to possible for hate to dissipate and disappear.

Comments